This past week we began a new Book of the Torah: Devarim ("Words") in Hebrew. In keeping with the month of Av, and Tisha B'Av, which is upon us, the words that open the Book are actually words of rebuke. Rashi points out that the rebuke, however, is said quite indirectly.

א. אֵלֶּה הַדְּבָרִים אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר משֶׁה אֶל כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן בַּמִּדְבָּר בָּעֲרָבָה מוֹל סוּף בֵּין פָּארָן וּבֵין תֹּפֶל וְלָבָן וַחֲצֵרֹת וְדִי זָהָב:

1. These are the words which Moses spoke to all Israel on the side of the Jordan in the desert, in the plain opposite the Red Sea, between Paran and Tofel and Lavan and Hazeroth and Di Zahav.

Rashi: These are the words: Since these are words of rebuke and he [Moses] enumerates here all the places where they angered the Omnipresent, therefore it makes no explicit mention of the incidents [in which they transgressed], but rather merely alludes to them, [by mentioning the names of the places] out of respect for Israel (cf. Sifrei)

Rashi also notes that these words were said to every single person of Israel:

Rashi: to all Israel: If he had rebuked only some of them, those who were in the marketplace [i.e., absent] might have said, “You heard from [Moses] the son of Amram, and did not answer a single word regarding this and that; had we been there, we would have answered him!” Therefore, he assembled all of them, and said to them, “See, you are all here; if anyone has an answer, let him answer!” - [from Sifrei]

Rashi then starts listing each of the places mentioned in the above verse and relating it to each of the major sins of the Jews in the desert. There is, however, one apparent gap in Rashi's analysis. Rashi begins by mentioning "in the desert," as the first place, related to the sin of having angered Hashem in the desert. In the above verse, though, "in the desert," is not the first place mentioned. Rather, the first geographic position noted is, "on the side of the Jordan," in Hebrew, "בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן (B'Ever HaYarden)."

Why did Rashi not link this place to one of the sins of the Jewish people. The answer perhaps is that this one is a reference not to any particular, but to the whole. It appears to be connected to the previous part of the verse, "to all Israel," as B'Ever HaYarden is reminiscent of the first partriarch of the Jewish people, Avraham Ha'Ivri (the Hebrew). Avraham is called Ha'Ivri because he stood on one side (believing in One G-d), while the entire world stood on the other. It may well also be a reference to the other side of the Jordan as well. The Jordan itself also symbolizes the all-encompassing whole. It runs from the Sea of Galilee, in the north of Israel all the way to its south, down to the Dead Sea.

There is however, also a hint to concept of the sins of Israel as a whole. The Hebrew word for Jordan, Yarden, is composed of the word Yarad (descended) and the final Nun, Nun-Sofit. The Nun is often associated with the word Nephilah, fall. However, the Nun is also associated with the redeemer, Moshe, and the final Nun with the final redeemer, Mashiach. (See Book 6, on the current, 14th cycle of 22 days of the year, here)

Every descent is only for the sake of a greater ascent. In order to learn how to walk, sometimes it is necessary to fall first. The main thing is to remain united, connected to the whole. If we do so, we are certain to merit

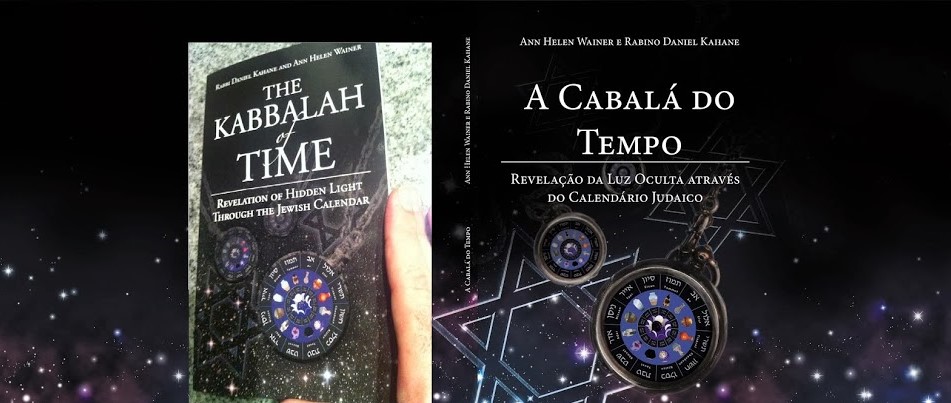

THE KABBALAH OF TIME: The Jewish Calendar is the master key to unlock the hidden rationale behind the formal structure of ancient sacred texts, as well as to understand and experience the most profound mystical concepts, which reveal the spiritual energy of each week, serving as a practical guide for self-analysis and development.

Weekly Cycle

Thursday, August 4, 2011

Monday, July 25, 2011

Words in the Desert: The Journey as the Cure and the Torah Portion of Ma'asei

This week's Torah portion speaks of the 42 journeys of the Jewish people in the desert. The second Rashi's opening comments make a parallel between Hashem and the Jewish people and a king that is taking his son back from a journey to find a cure for him:

1. These are the journeys of the children of Israel who left the land of Egypt in their legions, under the charge of Moses and Aaron.

RASHI: ... It is analogous to a king whose son became sick, so he took him to a far away place to have him healed. On the way back, the father began citing all the stages of their journey, saying to him, “This is where we sat, here we were cold, here you had a headache etc.” - [Mid. Tanchuma Massei 3, Num. Rabbah 23:3]

What is the cure and what is the illness? The Jewish people had not entered the Land yet. They were now at its border, ready to enter. Wouldn't it be more appropriate for Rashi to speak about an upcoming cure? And why are they on their way back?

The answer is that coming to Israel is the way back. The cure was the exile itself. Rebbe Nosson of Breslov speaks of how the exile took place because of a lack of faith. The exile and the wondering in the desert made it possible for that faith to be restored.

Similarly, the Counting of the Omer represents a period in which we cure ourselves. The Lubavitcher Rebbe points out that 49 is the gematria of Choleh, sick. Only after we are cured can we receive the Torah.

49 also equals the number of journeys (42) plus the number of Cana'anite nations to be conquered (7). The first 42 days of the omer, as well as the 42 journeys, are about internal rectification, the sefirot of Chesed through Yesod. From 43 to 49, we tackle our outwardly behavior, in dealing with the reality of the world around. That reality must be conquered, and that requires "curing" the Sefirah of Malchut, kingship. Don't be afraid to show the world who's Boss.

Observation: It is well known that G-d's seal is truth, Emet, in Hebrew. There is also a well known explanation that the word Emet itself represents truth because its gematria is 441, and 4+4+1 = 9. 9 is a number very much connected to truth because any multiple of 9, if you sum up their digits, is a multiple of 9. For example, 18 is 1+8=9, 27 is 2+7=9, 36, 45, and so on.

In addition to the above well known concept, there also appears to be a another reason 441 is chosen. 441, for the reasons explained above, is also a multiple of the number 9. But not just any multiple: 441 is 49 x 9.

1. These are the journeys of the children of Israel who left the land of Egypt in their legions, under the charge of Moses and Aaron.

RASHI: ... It is analogous to a king whose son became sick, so he took him to a far away place to have him healed. On the way back, the father began citing all the stages of their journey, saying to him, “This is where we sat, here we were cold, here you had a headache etc.” - [Mid. Tanchuma Massei 3, Num. Rabbah 23:3]

What is the cure and what is the illness? The Jewish people had not entered the Land yet. They were now at its border, ready to enter. Wouldn't it be more appropriate for Rashi to speak about an upcoming cure? And why are they on their way back?

The answer is that coming to Israel is the way back. The cure was the exile itself. Rebbe Nosson of Breslov speaks of how the exile took place because of a lack of faith. The exile and the wondering in the desert made it possible for that faith to be restored.

Similarly, the Counting of the Omer represents a period in which we cure ourselves. The Lubavitcher Rebbe points out that 49 is the gematria of Choleh, sick. Only after we are cured can we receive the Torah.

49 also equals the number of journeys (42) plus the number of Cana'anite nations to be conquered (7). The first 42 days of the omer, as well as the 42 journeys, are about internal rectification, the sefirot of Chesed through Yesod. From 43 to 49, we tackle our outwardly behavior, in dealing with the reality of the world around. That reality must be conquered, and that requires "curing" the Sefirah of Malchut, kingship. Don't be afraid to show the world who's Boss.

Observation: It is well known that G-d's seal is truth, Emet, in Hebrew. There is also a well known explanation that the word Emet itself represents truth because its gematria is 441, and 4+4+1 = 9. 9 is a number very much connected to truth because any multiple of 9, if you sum up their digits, is a multiple of 9. For example, 18 is 1+8=9, 27 is 2+7=9, 36, 45, and so on.

In addition to the above well known concept, there also appears to be a another reason 441 is chosen. 441, for the reasons explained above, is also a multiple of the number 9. But not just any multiple: 441 is 49 x 9.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Words in the Desert: Verbal Agreements and the Torah Portion of Matot

This week's Torah portion contains a striking parallel between how it begins and how it ends. The portion begins as follows:

2. Moses spoke to the heads of the tribes of the children of Israel, saying: This is the thing the Lord has commanded. 3. If a man makes a vow to the Lord or makes an oath to prohibit himself, he shall not violate his word; according to whatever proceeded from his mouth, he shall do.

ב. וַיְדַבֵּר משֶׁה אֶל רָאשֵׁי הַמַּטּוֹת לִבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר זֶה הַדָּבָר אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יְהֹוָה

ג. אִישׁ כִּי יִדֹּר נֶדֶר לַיהֹוָה אוֹ הִשָּׁבַע שְׁבֻעָה לֶאְסֹר אִסָּר עַל נַפְשׁוֹ לֹא יַחֵל דְּבָרוֹ כְּכָל הַיֹּצֵא מִפִּיו יַעֲשֶׂה:

24. So build yourselves cities for your children and enclosures for your sheep, and what has proceeded from your mouth you shall do."

כד. בְּנוּ לָכֶם עָרִים לְטַפְּכֶם וּגְדֵרֹת לְצֹנַאֲכֶם וְהַיֹּצֵא מִפִּיכֶם תַּעֲשׂוּ:

We shall build sheepfolds for our livestock here: They were more concerned about their possessions than about their sons and daughters, since they mentioned their livestock before [mentioning] their children. Moses said to them, “Not so! Treat the fundamental as a fundamental, and the matter of secondary importance as a matter of secondary importance. First ‘build cities for your children,’ and afterwards 'enclosures for your sheep’” (verse 24) - [Mid. Tanchuma Mattoth 7]

Another comment made by Rashi, perhaps not as famous, is on the phrase that links the beginning of the Parasha to its end:

and what has proceeded from your mouth you shall do: for the sake of the Most High [God], for you have undertaken to cross over for battle until [the completion of] conquest and the apportionment [of the Land]. Moses had asked of them only “and… will be conquered before the Lord, afterwards you may return,” (verse 22), but they undertook,“until… has taken possession” (verse 18). Thus, they added that they would remain seven years while it was divided, and indeed they did so (see Josh. 22).

Moshe is holding the Tribes accountable for an additional condition, which Moshe himself had not asked of them. Moshe asked that they stay until the Land be conquered, but they vowed to stay until the Land had been properly apportioned, which required that they stay an additional seven years.

The question is: how could Moshe hold them to this requirement if in fact they did not pledge to this in the form of a vow. All they said was, "We shall not return to our homes until each of the children of Israel has taken possession of his inheritance." One could even argue that they were still "negotiating" with Moshe.

From here we learn again, what is the main theme of the Book of Bamidbar: the tremendous power of words. (Midbar means desert, but has at its root Davar, word). One has to be so very careful about what one says, certainly involving the bad, but regarding the good as well. In Jewish law, any expression of willingness to perform a mitzvah or good deed brings upon an obligation.

Moshe is therefore able to take something that seemed abstract and perhaps even out-of-place in the outset of the parashah, and drive it home in the most practical of ways: a few added words led to a commitment to stay seven more years away from their families and livestock, and as Rashi concludes, "indeed they did so."

Monday, July 11, 2011

Words in the Desert: Earning One's Place and the Torah Portion of Pinchas

B"H

This week's Torah portion begins with the description of the great reward given to Pinchas for his dramatic act of killing the prince of the tribe of Shimon and the Midianite princess with whom he was openly having relations. In doing so, he stopped the plague that had engulfed the Jewish people. The plague had resulted also from the worshipping of the Midianite idol known as Baal Peor. The reward that Pinchas receives is nothing less than Kehunah, the priesthood.

There is, however, somewhat of mystery to the reward given. One would think that Pinchas, son of Elazar, the Kohen Gadol, would already be considered a Kohen. Rashi explains:

10. The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: 11. Phinehas the son of Eleazar the son of Aaron the kohen has turned My anger away from the children of Israel by his zealously avenging Me among them, so that I did not destroy the children of Israel because of My zeal. 12. Therefore, say, "I hereby give him My covenant of peace. 13. It shall be for him and for his descendants after him [as] an eternal covenant of kehunah, because he was zealous for his God and atoned for the children of Israel."

RASHI: an eternal covenant of kehunah: Although the kehunah had already been given to Aaron’s descendants, it had been given only to Aaron and his sons who were anointed with him, and to their children whom they would beget after their anointment. Phinehas, however, who was born before that and had never been anointed, had not been included in the kehunah until now. And so, we learn in [Tractate] Zevachim [101b],“Phinehas was not made a kohen until he killed Zimri.”

Why is it that Aaron's sons, as well as future generations, received the priesthood automatically, while Pinchas had to earn it?

We know that in spirituality, certain positions and even character traits are inherited. Judaism itself is something inherited from our forefathers, Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaakov. Those that wish to join our people (converts), must earn that right through what is often a long and cumbersome process.

The Torah states that the priesthood was given to Yocheved for her bravery in saving the Jewish newborn babies and ignoring Pharaoh's orders. This reward materialized with Aharon, her eldest son, who showed great initiative in meeting his brother Moshe and being an essential part of the redemption process. As we learn in Pirkei Avot, Aharon himself embodied the ideals of the covenant of peace: He "loves peace and pursues peace, loves the creations and brings them closer to the Torah."

Why then was Pinchas left out? One can certainly assume that he had already inherited the same qualities (from Yocheved and Aharon) that Elazar and the other Kohanim had inherited.

Perhaps the answer is that Hashem wanted to give Pinchas an additional reward and connection to the Kehunah. To earn something, as opposed to getting it as an inheritance, is certainly a lot more special. Yes, the qualities were there all along. However, because Pinchas was able to specifically do something to become a Kohen, it was that much more special.

The same is true regarding converts, as well as our final redemption. Yes, converts have the qualities necessary to become Jewish all along (their souls too were at Sinai), but when they become Jewish through their own efforts, it's that much more special. Yes, Hashem has the ability to redeem us at any moment, but when we put in our own efforts, and share in its coming into being, we will value it that much more. And so will He.

This week's Torah portion begins with the description of the great reward given to Pinchas for his dramatic act of killing the prince of the tribe of Shimon and the Midianite princess with whom he was openly having relations. In doing so, he stopped the plague that had engulfed the Jewish people. The plague had resulted also from the worshipping of the Midianite idol known as Baal Peor. The reward that Pinchas receives is nothing less than Kehunah, the priesthood.

There is, however, somewhat of mystery to the reward given. One would think that Pinchas, son of Elazar, the Kohen Gadol, would already be considered a Kohen. Rashi explains:

10. The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: 11. Phinehas the son of Eleazar the son of Aaron the kohen has turned My anger away from the children of Israel by his zealously avenging Me among them, so that I did not destroy the children of Israel because of My zeal. 12. Therefore, say, "I hereby give him My covenant of peace. 13. It shall be for him and for his descendants after him [as] an eternal covenant of kehunah, because he was zealous for his God and atoned for the children of Israel."

RASHI: an eternal covenant of kehunah: Although the kehunah had already been given to Aaron’s descendants, it had been given only to Aaron and his sons who were anointed with him, and to their children whom they would beget after their anointment. Phinehas, however, who was born before that and had never been anointed, had not been included in the kehunah until now. And so, we learn in [Tractate] Zevachim [101b],“Phinehas was not made a kohen until he killed Zimri.”

Why is it that Aaron's sons, as well as future generations, received the priesthood automatically, while Pinchas had to earn it?

We know that in spirituality, certain positions and even character traits are inherited. Judaism itself is something inherited from our forefathers, Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaakov. Those that wish to join our people (converts), must earn that right through what is often a long and cumbersome process.

The Torah states that the priesthood was given to Yocheved for her bravery in saving the Jewish newborn babies and ignoring Pharaoh's orders. This reward materialized with Aharon, her eldest son, who showed great initiative in meeting his brother Moshe and being an essential part of the redemption process. As we learn in Pirkei Avot, Aharon himself embodied the ideals of the covenant of peace: He "loves peace and pursues peace, loves the creations and brings them closer to the Torah."

Why then was Pinchas left out? One can certainly assume that he had already inherited the same qualities (from Yocheved and Aharon) that Elazar and the other Kohanim had inherited.

Perhaps the answer is that Hashem wanted to give Pinchas an additional reward and connection to the Kehunah. To earn something, as opposed to getting it as an inheritance, is certainly a lot more special. Yes, the qualities were there all along. However, because Pinchas was able to specifically do something to become a Kohen, it was that much more special.

The same is true regarding converts, as well as our final redemption. Yes, converts have the qualities necessary to become Jewish all along (their souls too were at Sinai), but when they become Jewish through their own efforts, it's that much more special. Yes, Hashem has the ability to redeem us at any moment, but when we put in our own efforts, and share in its coming into being, we will value it that much more. And so will He.

Monday, July 4, 2011

Words in the Desert: Horrible Bosses and the Torah Portion of Balak

B”H

This week's Torah portion is about the greatest prophet among the gentiles, Bilaam, and the evil king Balak, that hired him to curse the Jewish people. Instead of a curse, Bilaam delivers one of the most beautiful blessings ever delivered to our people.

The Shem M'Shmuel states that Balak and Bilaam were trying hard to nullify everything that Avraham, Itzchak and Yaakov accomplished, and prevent the Jewish people from entering our Promised Land.

The parallels between Avraham and Bilaam are quite extraordinary. Avraham is told that whoever blesses him will be blessed and whoever curses him will be cursed. About Bilaam it states, whoever he curses will be cursed and whoever he blesses will be blessed.

When embarking on a mission, the Torah states that Avraham arose early in the mourning and saddled his donkey. Almost the same words are used in describing Bilaam's preparations:

21. In the morning Balaam arose, saddled his she-donkey and went with the Moabite dignitaries.

Rashi picks up on this parallel and comments on the above verse:

saddled his she-donkey: From here [we learn] that hate causes a disregard for the standard [of dignified conduct], for he saddled it himself. The Holy One, blessed is He, said, “Wicked one, their father Abraham has already preceded you, as it says, 'Abraham arose in the morning and saddled his donkey’” (Gen. 22:3). - [Mid. Tanchuma Balak 8, Num. Rabbah 20:12]

Another striking parallel is that both men took with them two young men to accompany them in their mission. Rashi's comments in both passages regarding this are very similar, but far from identical. Regarding Abraham, it states:

3. And Abraham arose early in the morning, and he saddled his donkey, and he took his two young men with him and Isaac his son; and he split wood for a burnt offering, and he arose and went to the place of which God had told him.

RASHI - his two young men: Ishmael and Eliezer, for a person of esteem is not permitted to go out on the road without two men, so that if one must ease himself ["go to the bathroom"] and move to a distance, the second one will remain with him.

As Pirkei Avot makes clear, we must always strive to be students of Avraham, staying holy and pure, and deserving of the highest blessings, that had to be brought down through the impure mouth of the unholy Bilaam.

This week's Torah portion is about the greatest prophet among the gentiles, Bilaam, and the evil king Balak, that hired him to curse the Jewish people. Instead of a curse, Bilaam delivers one of the most beautiful blessings ever delivered to our people.

The Shem M'Shmuel states that Balak and Bilaam were trying hard to nullify everything that Avraham, Itzchak and Yaakov accomplished, and prevent the Jewish people from entering our Promised Land.

The parallels between Avraham and Bilaam are quite extraordinary. Avraham is told that whoever blesses him will be blessed and whoever curses him will be cursed. About Bilaam it states, whoever he curses will be cursed and whoever he blesses will be blessed.

When embarking on a mission, the Torah states that Avraham arose early in the mourning and saddled his donkey. Almost the same words are used in describing Bilaam's preparations:

21. In the morning Balaam arose, saddled his she-donkey and went with the Moabite dignitaries.

Rashi picks up on this parallel and comments on the above verse:

saddled his she-donkey: From here [we learn] that hate causes a disregard for the standard [of dignified conduct], for he saddled it himself. The Holy One, blessed is He, said, “Wicked one, their father Abraham has already preceded you, as it says, 'Abraham arose in the morning and saddled his donkey’” (Gen. 22:3). - [Mid. Tanchuma Balak 8, Num. Rabbah 20:12]

Another striking parallel is that both men took with them two young men to accompany them in their mission. Rashi's comments in both passages regarding this are very similar, but far from identical. Regarding Abraham, it states:

3. And Abraham arose early in the morning, and he saddled his donkey, and he took his two young men with him and Isaac his son; and he split wood for a burnt offering, and he arose and went to the place of which God had told him.

RASHI - his two young men: Ishmael and Eliezer, for a person of esteem is not permitted to go out on the road without two men, so that if one must ease himself ["go to the bathroom"] and move to a distance, the second one will remain with him.

Regarding Bilaam:

22. God's wrath flared because he was going, and an angel of the Lord stationed himself on the road to thwart him, and he was riding on his she-donkey, and his two servants were with him.

RASHI - and his two servants were with him: From here we learn that a distinguished person who embarks on a journey should take two people with him to attend to him, and then they can attend to each other.

Why does Rashi change the wording, regarding Bilaam. Why is it necessary to state that the servants of Avraham will need to distance themselves and go to the bathroom, while regarding Bilaam it says that they will attend to each other. Wouldn't one expect the more "respectful" (non-bathroom) language to be used regarding Avraham and not Bilaam?

The answer is that Avraham's encampment, like that of the Jewish people, was holy. One of the laws regarding a holy encampment is that one may not defecate among it. One must distance oneself and cover the excrement. The servants of Avraham would have to distance themselves when going to the bathroom. Although Bilaam praises the Jewish encampment for being holy, his own encampment was not. Quite the contrary, it was of the utmost impurity, and there was no need whatsoever to distance it from filth.

Similarly, Avraham's servants had a gracious and generous master, someone who knew their limits and would not overwhelm them. When one had to leave, the other would be able to attend to him. Bilaam was self-centered egotistical and the servants needed each other just to be able to cope with their master's vain demands, which most likely were anything but realistic, as we see regarding his interaction with his mule.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

DOWNLOAD A FREE COPY OF PEREK SHIRAH HERE!